Who is afraid of the dark?

/There is a great need for anthropized spaces to be comfortable and give opportunities for reflection and introspection. Cities have existed for several millennia and have always represented, despite the simplicity of their earliest period, physical realities that shape and preserve our spiritual, social and cultural identity. Yet, recently, urban centers are being transformed into mere systems of connection between residences, activities and services, in which stressors that become chronic and turn into neurosis and schizophrenia are silently triggered.

BUdapest at dusk Img by Giulia scione

Urban walks are very powerful in marking our daily experience and shaping our life, as the systemicity and constancy of their frequency are stronger than the most regenerating but sporadic naturalistic experiences. The biophilic hypothesis explains how beneficial and therefore necessary it is to enrich the urban landscape with natural elements, such as water and green, but very little is said about how dangerous it is to deprive man of a fundamental experience for his life cycle and the physiology of his visual system: the dark.

The dark has become the scapegoat of the degradation phenomenon of many urban areas, since the poorly lit areas seem to get a higher perception of risk, which lead to abandon and to degradation. Therefore urban lighting has become a discriminating factor for the quality of life of a neighborhood: the more the areas are illuminated, the more inviting they are, and the greater the success guaranteed for commercial activities. The glow of the metropolitan areas of today produces a diffused light on a territorial scale of 4 lux, which is equivalent to 4 times the glow generated by the full moon. A distorted lighting condition may have an impact on our organism.

Our visual system has been programmed for a photopic (diurnal) vision, but also for a scotopic (nocturnal) vision. The human eye has two distinct types of photoreceptors at the bottom of the retina for these two visual modes. The cones respond to the colors, the shapes, the details of the central view, while the “slower” rodes, responsible of the peripheral sight, respond better to dim light and let us grasp the movement and perceive the surrounding reality in a typical night sky condition.

Does everyday life still offer experience of the dark or this is another important natural condition that is denied to us?

Back to the previous statement about our need to live in a more intimate and comfy environment, it must be said that the concept of darkness is closely linked to the experience of silence, of the vague and therefore of tranquility.

Dark Art Room by

““Do we need darkness to perceive more?””

This is a question asked by C. Tomara in her article about impressions on the PLDC2019 event, in particular for the Dark Art Room installation. Here the author points out how wonderful and at the same time under stimulated it is our visual ability to adapt to the dark.

This consideration reminded me of my recent personal and quite different experience. Recently I found myself retracing a street of my hometown, which was completely dark due to a temporary blackout. My mental state in that moment, quite nostalgic and slightly melancholy, distracted me from the fear of continuing my journey, and despite the darkness, I felt a strong invitation to throw myself into it, to try a new (or forgotten) feeling. The familiarity of the road has certainly helped in reducing the perception of danger, and, instead, let me enjoy the positive feeling of quiet. I felt a strong contact with nature and the positivity of a heartening experience, capable of generating detachment from the anthropized, although I was fully surrounded by cemented volumes, I could feel the asphalt under my feet and see cars driving next to me.

I had a very similar experience, as adult, the first time I walked through fog. The impossibility of perceiving the details of objects and a pervading and diffuse light not returning any depth of the visual field, made me isolate from the reality of the external world and drove me to dialogue with myself.

Foggy urban street

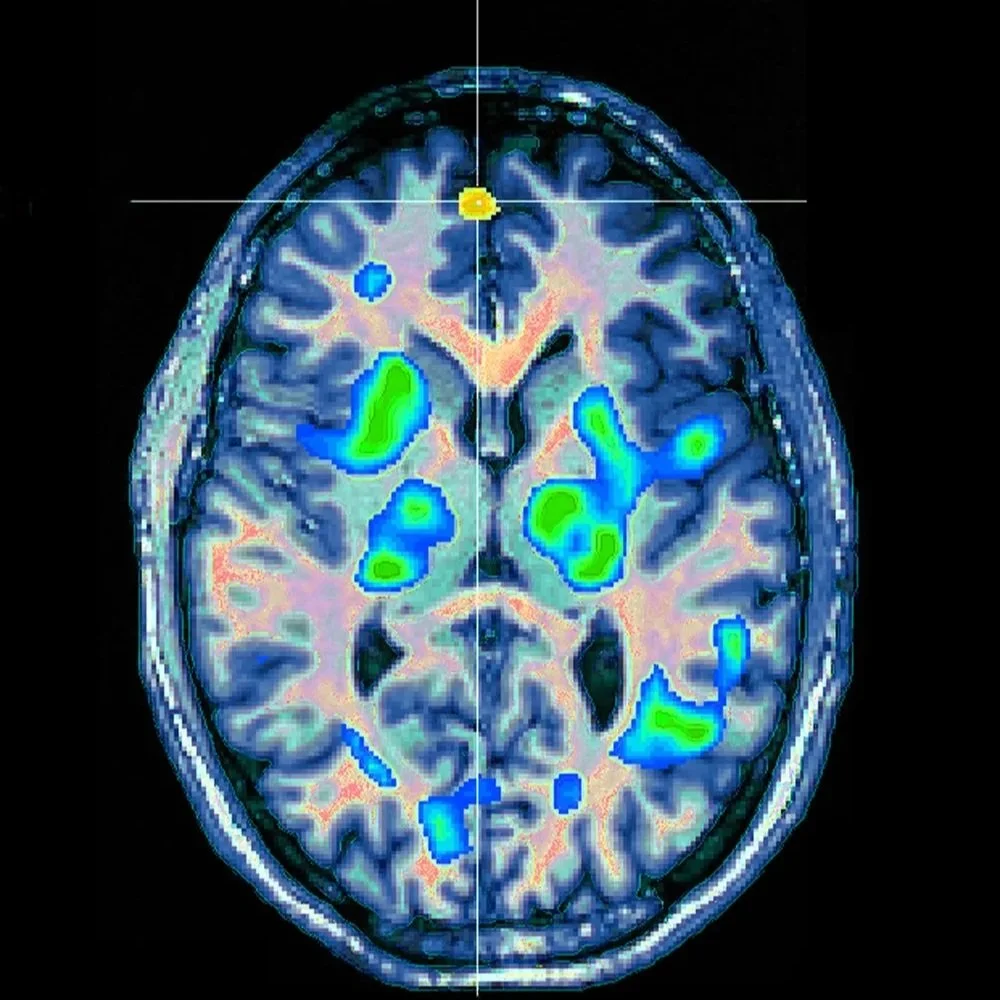

Science could explain this phenomenon of empathy. During the phase of falling asleep, or even that of daydreaming, electroencephalography (EEG), which records the electrical activity of the brain, detects an accentuated activity of the alpha waves in conjunction with a certain visual torpor. We can assume that, vice versa, by creating torpor in vision we can trigger pseudo-dream mental states. The explanation could be in the fact that a poor restitution of the details, of the shapes, of the contrast due to a diffused light on all our visual field, brings us into a dimension detached from reality as we normally perceive it, because it is not typical of the everyday experience.

The visual experience in the diurnal fog is neither the scotopic vision -because it is not a matter of darkness- nor does it allow the central vision, capable of restoring the details and colors of things. Everything is then shaded in a timeless and a-spacial dimension that inevitably leads to a meditative introspection, even more than darkness can make.

The difference between the experience in the dark and the fog lies in the fact that in the first case we can count on minimal but effective space references: just a 0.006 Lux light, which is typical of the night with a starry sky, allows us, through the slow but effective rods activation, to perceive shapes, contours, movements, and therefore to decode the body language of the people around revealing their intentions and emotions. Our being social animals predisposes us to the interpretation of the visual sets, in a sort of simultaneous elaboration of objective elements of the visual scene and the memories and knowledge recalled and combined by the associative visual cortex.

Urban light design, supported by psychophysiological reasearch, is an excellent design tool, an opportunity to mediate strong and realistic signs with induced and whispered messages, inorder to return a visual set as reassuring as possible, caable of transforming the experience of darkness from uniquely threatening to a positive opportunity for relaxing dialogue with oneself.

We should not be afraid of the dark,and not only because we need it, to fall asleep and constantly align our circadian rhythm, but also because our physiology provide the right tools to engage with it. Darkness engage our rods, prevent their atrophy, and above all, it let us look and see better inside and outside ourselves.